An aversion to tax increases has long been one of the Republican Party’s core pillars, but tradition was upended in recent weeks as discussions of a potential new millionaires’ tax hike hit Capitol Hill.

It’s baffled some members of the GOP’s old guard, though Republican operatives who spoke with Fox News Digital were less surprised. They said those conversations were largely ushered in by the party’s growing populist wing.

“I’m not sure if I’m surprised anymore, because the party has changed so much in just a short period of time. But it is noteworthy,” longtime GOP strategist Doug Heye told Fox News Digital.

Heye recalled his time as a senior House leadership aide in 2012, when a Republican proposal for a uniform tax rate for people making under $1 million per year was blown up “by a rebellion within our own ranks” over raising taxes.

“It all exploded in our faces,” he said. “And now this is what more and more of those Republicans who rejected the idea in 2012 want to do.”

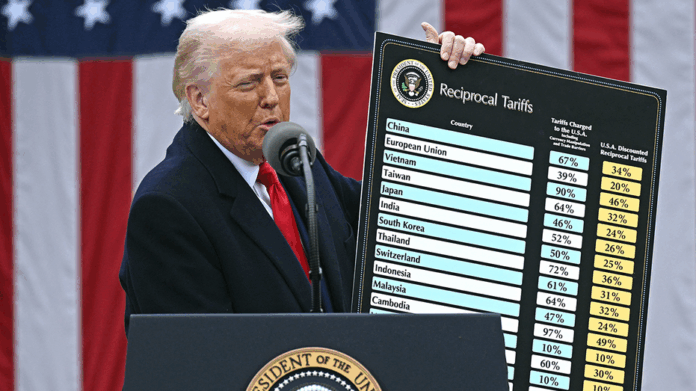

Sources told Fox News Digital this month that the White House was socializing a plan among Republicans to create a new 40% tax bracket for people making more than $1 million.

Various reported plans floated among House Republicans included raising taxes on the ultra-wealthy to rates between 38% and 40%.

Former House Speaker Newt Gingrich has been seeking to quash that this week, even posting a purported message from President Donald Trump himself on X that said, “If you can do without it, you’re probably better off trying to do so.”

Fox News Digital reached out to the White House on Wednesday morning for comment on Gingrich’s note, including the context of the message and why Trump described that he would “love” increasing taxes, but did not receive a reply.

The top income tax rate is currently about 37% on $609,351 in earnings for a single person or $731,201 for married couples. It was lowered from just over 39% by Trump’s 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act.

“The politics are good for raising taxes on wealthy Americans,” said John Feehery, a partner at EFB Advocacy and veteran of House GOP leadership staff. “The downside is it does have an impact on economic growth. So if you want the cheap political score, that’s the way to go. On the other hand, if you want a solid economy where people are working, you want to be careful on how you do that.”

Asked if the discussions caught him off guard, Feehery said, “I’m not surprised by it because Trump is such a populist, and he has a lot of folks who are populist.”

He signaled the appeal of higher taxes for the wealthy was born from that shift.

“If you look at the constituencies, the biggest constituency, it’s really interesting because the parties have kind of changed,” he continued. “It used to be the country-club Republicans and working-class Democrats; now it’s working-class Republicans and country-club Democrats.”

Heye said when asked about the increase in tax hike talks, “I think it’s a mixture of Trump and populism.”

“Raising taxes used to be an anathema to Republicans, and you know, when George Bush did it after saying ‘Read my lips,’ that was the beginning of the end of his presidency,” Heye said. “That world just doesn’t exist anymore.”

House GOP leaders have publicly made clear that they’re opposed to raising taxes on anyone. But Republicans must find a way to pass Trump’s budget, including new tax policies eliminating duties on tipped and overtime wages, while meeting conservatives’ demand to cut at least $1.5 trillion in government spending to make up for it.

House Freedom Caucus Chair Andy Harris, R-Md., previously signaled that he is open to the idea if spending cuts can’t be reached by other means.

“What I’d like to do is, I’d actually like to find spending reductions elsewhere in the budget, but if we can’t get enough spending reductions, we’re going to have to pay for our tax cuts,” Harris told “Mornings with Maria” on FOX Business last week.

SCOOP: PENCE URGES REPUBLICANS TO HOLD THE LINE ON TAX HIKES FOR THE RICH AS TRUMP WEIGHS OPTIONS

“Before the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, the highest tax bracket was 39.6%; it was less than $1 million. Ideally, what we could do – again, if we can’t find spending reductions – we say, ‘OK, let’s restore that higher bracket, let’s set it at maybe $2 million income and above’ to help pay for the rest of the president’s agenda.”

Rep. Dan Meuser, R-Pa., similarly floated raising the top tax bracket to 38.6%.

He later told Fox News Digital in a statement, “I believe we must help the president deliver on his promise of a tax and regulatory plan that supports pro-American economic and manufacturing growth, and delivers for the vast majority of Americans – while creating savings and promoting fiscal responsibility. Any adjustments in taxes to accomplish these goals should be considered.”

Both Meuser and Harris declined to provide more comment for this story.

Former Vice President Mike Pence, who refers to the 2017 tax cuts as the “Trump-Pence tax cuts,” last week urged House Republicans to stand firm against raising taxes on the country’s top earners and to make the 2017 tax cuts permanent.

One House GOP lawmaker told Fox News Digital last week that reaction among their colleagues to possible tax hikes was “mixed.”

But a former Republican member was skeptical on Wednesday.

“Raising taxes is a short-term high, which ultimately does more harm than good,” the former House Republican said. “This strategy is contrary to conservative values.”

CLICK HERE TO GET THE FOX NEWS APP

Meanwhile, Marc Goldwein, senior policy director at the nonpartisan Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget, said it was “healthy” that lawmakers are entertaining fiscal ideas outside their party norms.

He was wary about the push for a tax hike, however.

“I’m not a fan of doing things that look fiscally good at the same time that you’re doing things that actually are fiscally bad … on top of that, I don’t think raising tax rates is the best way to raise revenue,” Goldwein said. “But with those two things said, I think it is very healthy move that the GOP kind of is talking about that rates actually can go in both directions.”

Fox News Digital reached out to Gingrich for an interview for this story but did not receive a response.

Fox News Digital’s Emma Colton contributed to this report.