President Donald Trump has championed tariffs as the economic tool that will bring parity to the nation’s chronic trade deficit with foreign countries while boosting U.S. jobs and the economy. But many of Trump’s tariff polices have been walked back or paused after going into effect.

“I will immediately begin the overhaul of our trade system to protect American workers and families. Instead of taxing our citizens to enrich other countries, we will tariff and tax foreign countries to enrich our citizens,” Trump declared in his inaugural address Jan. 20, teeing up an onslaught of tariff policies that will take effect in the coming weeks and months.

Tariffs are taxes levied on imported goods and services that historically have contributed to a nation’s federal tax revenue. Developed countries, however, have since moved away from relying on tariffs as a main source of federal funding and have shifted to other forms of taxes — such as income, payroll or sales taxes.

On Tuesday, which marked Trump’s 100th day back in the Oval Office, Trump signed an executive action easing tariffs targeting car manufacturers as he headed to Michigan, historically the heart of the American auto industry, for a rally celebrating his return to the White House.

PRESIDENT DONALD TRUMP’S FIRST 100 DAYS: COMPANIES THAT WILL INVEST $1B OR MORE IN THE US

The upcoming auto plan will keep a 25% tariff on imported cars and a 25% tariff on imported auto parts but will offer offset credits to U.S. manufacturers for a two-year period in an effort to bolster the U.S. supply chain of car parts and encourage manufacturing in the U.S., according to the administration.

The plan will also not stack both auto and steel and aluminum tariffs on the auto industry. Only the higher tariff will be applied to car manufacturers, not a combined tariff.

The announcement is the latest of Trump walking back, pausing or easing tariffs as he looks to even the trade playing field for the U.S., while encouraging U.S. manufacturing and job creation. Industries that manufacture products on U.S. soil do not face any tariffs.

A White House official who spoke to Fox News Digital explained that while the past few months of tariff changes might seem chaotic in their entirety, each change was born out of a need to be flexible and an effort to bring manufacturing and jobs into the U.S. while ending the nation’s chronic trade deficit. The official noted that, as tariffs took effect, many nations and industry leaders have made good-faith efforts to negotiate terms favorable to the U.S., adding to the tariff changes.

AMAZON DENIES TARIFF PRICING PLAN THAT WHITE HOUSE CALLED ‘HOSTILE AND POLITICAL’

Trump’s tariff policies overwhelmingly focused on China, Mexico and Canada at the start of his second administration, as he looked to crack down on illegal immigration. It also was an attempt to stem the flow of the deadly synthetic opioid fentanyl, which overwhelmingly originates in China, from coming across the northern and southern borders.

Citing the threat of illegal aliens in the U.S. and the flow of fentanyl, Trump declared a national emergency in February under the International Emergency Economic Powers Act and imposed a 25% tariff on imports from Canada and Mexico and a 10% additional tariff on imports from China.

The tariffs sparked swift outrage from the three nations, and Trump paused the tariffs on Canada and Mexico for 30 days after the nations agreed to concessions, such as sending additional security personnel to their respective borders with the U.S.

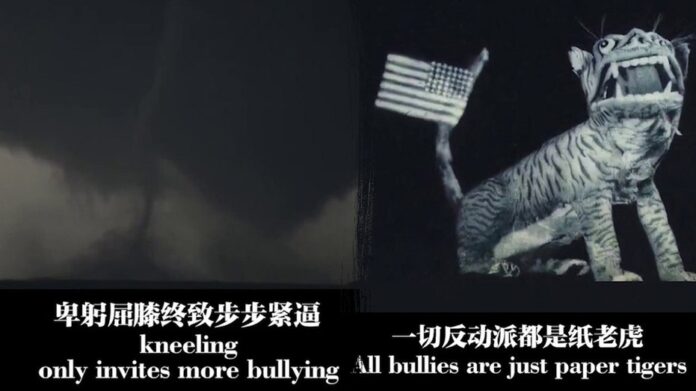

China, on the other hand, imposed tariffs on some U.S. imports in response to Trump’s tariffs. China’s Finance Ministry said Feb. 4, shortly after the tariffs started, that it would impose a tariff of 15% for coal and liquefied natural gas and 10% for crude oil, agricultural equipment and large-engine cars imported from the U.S.

GROCERY GIANT WARNS ITS SUPPLIERS THAT SUPERMARKET WON’T BE ACCEPTING TARIFF-RELATED PRICE HIKES

The administration official who spoke to Fox Digital pointed to the tariff changes for Mexico and Canada as part of negotiations to secure the border after Trump declared a national emergency under the International Emergency Economic Powers Act.

The tariffs on Mexico and Canada went into effect March 4 after the pause, while the tariffs on China were increased to 20%. A day later, after speaking with auto industry officials from Ford, General Motors and Stellantis, Trump walked back the tariffs if they affected the auto industry, granting a one-month exemption to tariffs “on any autos” from the two countries that abide by the 2020 U.S.-Mexico-Canada Agreement’s rules of origin.

Those rules were established under the first Trump administration, White House press secretary Karoline Leavitt said at a news conference at the time.

On March 6, Trump again walked back the 25% tariffs on many imports from Canada and Mexico while praising Mexican President Claudia Sheinbaum for helping secure the U.S.-Mexico border. He postponed the tariffs for 30 days and touted that his highly anticipated reciprocal tariff plan would take effect in the coming weeks.

DONALD TRUMP SHOULD BE PRAISED FOR SIGNALS HE MIGHT COOL TARIFF FIGHT, WASHINGTON POST EDITORIAL PRAISES

“I did this as an accommodation, and out of respect for, President Sheinbaum,” Trump said on Truth Social of the March 6 tariff pause. “Our relationship has been a very good one, and we are working hard, together, on the Border.”

While announcing and imposing tariffs on nations such as Mexico and Canada, Trump previewed a reciprocal tariff plan that would take effect April 2.

“On trade I have decided for purposes of fairness, that I will charge a reciprocal tariff — meaning whatever countries charge the United States of America, we will charge them no more, no less,” Trump said at the White House in February. “In other words, they charge us a tax or tariff, and we charge them the exact same tax or tariff. Very simple.”

Trump announced his highly anticipated reciprocal tariff plan as part of his “Liberation Day” announcement April 2. Trump announced customized tariffs on dozens of nations to help bring parity to what he said were decades of foreign nations installing trade barriers on U.S. goods, while also imposing a 10% baseline tariff on all countries.

“For nations that treat us badly, we will calculate the combined rate of all their tariffs, nonmonetary barriers and other forms of cheating,” he said. “And because we are being very kind, we will charge them approximately half of what they are and have been charging us. So, the tariffs will be not a full reciprocal. I could have done that. Yes. But it would have been tough for a lot of countries.”

TRUMP SAYS INCOME TAX CUTS, AND PERHAPS ELIMINATION, COMING DUE TO TARIFFS

The EU for example, was hit with a 20% tariff in the reciprocal tariff plan, compared to its 39% tariffs on the U.S., while Japan saw 24% tariffs compared to the 46% the country charges the U.S. China was hit with an additional 34% tariff, compared to the 67% it charges the U.S.

The same day the reciprocal tariffs were about to take effect April 9, Trump announced a 90-day pause on the customized duty taxes he had imposed on dozens of nations, which was an abrupt change of course from his previous comments that there would be no pause to those tariffs, only negotiations. The pause did not include the 10% baseline tariff on all nations.

“You have to have flexibility,” Trump told the media when asked about his credibility after pausing the tariffs. “I could say there’s a wall. … Sometimes, you have to go around or under the wall. Financial markets change. Look how much they changed. I think the word would be ‘flexible.’ You have to be flexible.”

White House officials told Fox News Digital at the time that dozens of countries had reached out to the White House looking to make good-faith deals, and that the administration was zeroing in on renegotiating more favorable deals for the U.S.

Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent indicated in recent days that trade negotiations with at least South Korea and India are entering the final stages.

Other tariffs, such as a 25% tax on all steel and aluminum imports or the 10% baseline tariff on foreign nations, have remained in effect without change.

Trump has touted that with increased revenue from tariffs, U.S. citizens could see lower taxes and the possible elimination of the income tax.

“When Tariffs cut in, many people’s Income Taxes will be substantially reduced, maybe even completely eliminated. Focus will be on people making less than $200,000 a year,” Trump wrote in a post on Truth Social April 13.

“Also, massive numbers of jobs are already being created, with new plants and factories currently being built or planned. It will be a BONANZA FOR AMERICA!!! THE EXTERNAL REVENUE SERVICE IS HAPPENING!!!”

Fox News Digital’s Eric Revell contributed to this report.