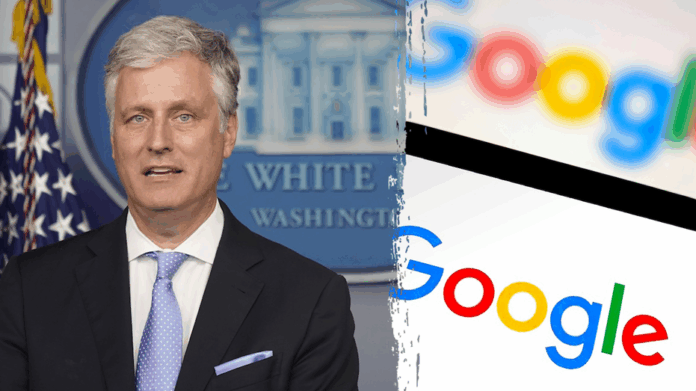

FIRST ON FOX – President Donald Trump‘s former national security advisor is sounding the alarm about the Justice Department’s proposal to break up Google’s illegal monopoly on online search, saying in a letter to White House leaders that the government’s proposal is overly broad and poses “drastic” and far-reaching national security risks.

In a letter to the White House National Security Council, obtained by Fox News Digital, Trump’s former national security advisor, Robert O’Brien, argued that the Biden-era DOJ framework is in “direct conflict” with Trump’s policy priorities, and risks hobbling U.S. competition with China in a high-stakes race to develop new and advanced technology.

The U.S., he said, “now finds itself in a literal ‘technology race’ – as significant and critical to our nation’s strength, and the Trump Administration’s objectives, as the ‘arms race’ of the past century,” O’Brien said.

“To prevail, the U.S. must maintain and expand its global leadership in key technologies.”

TRUMP WAGERS US ECONOMY IN HIGH-STAKES TARIFF GAMBLE AT 100-DAY MARK

The letter was sent to White House national security advisor Mike Waltz before he was ousted from his role Thursday along with his deputy, Alex Wong, in the wake of the Signal controversy earlier this year. It was not immediately clear who Trump planned to install as his replacement. A copy was also sent to U.S. Attorney General Pam Bondi.

News of the letter, first reported by Fox News Digital, comes as lawyers for the Justice Department and Google continue to spar in federal court over how far Google should go to break up what a judge ruled last year to be its illegal monopoly on online search.

O’Brien in his letter said the plans proposed by the Biden-era DOJ would cripple Google’s ability to compete or innovate on the global stage – undermining U.S. leadership on cutting-edge technologies, such as AI and quantum computing, in its race against China, and presenting grave new economic and national security risks.

DOJ’s Antitrust Division is “aggressively pursuing the misguided policies of the prior Biden Administration and its European-like approach to crippling our nation’s largest and most robust technology companies,” O’Brien said. “By ignoring their enormous value to our country’s strength, the Antitrust Division is seeking, through draconian remedies, to import European-style regulatory restrictions and prohibitions at home here in the Google Search case.”

He also urged the Trump-led Department of Justice to review the framework to restructure Google’s search engine and amend it in a way that would still allow the company to compete.

“Splitting Google into smaller companies and forfeiting its intellectual property would weaken U.S. competitiveness against the giant, state-backed Chinese tech companies, since, separated entities would lack the enormous resources needed,” O’Brien said.

“Experts in multiple fields critical to national security confirm these basic principles and loudly address the concern that handcuffing our high-tech powerhouses would undermine U.S. leadership and superiority in these key technologies, and risk ceding the world’s technology leadership to China,” he said.

TRUMP DOJ’S PLAN TO RESTRUCTURE GOOGLE HURTS CONSUMERS, NATIONAL SECURITY, SAYS EXEC: ‘WILDLY OVERBROAD’

The letter comes as Google and the Justice Department continue to spar in federal court in a so-called “remedies hearing” to break up what U.S. District Judge Amit Mehta ruled last summer was Google’s illegal monopoly in the online search engine space.

The two sides presented the court with starkly different plans for how they believe Google should go about resolving its monopoly – the first successful antitrust lawsuit brought by the U.S. against a major tech company since U.S. v. Microsoft in 2001.

Justice Department lawyers said Google should be required to sell off its Chrome browser, share years of its consumer data with competitors, and potentially sell Android, Google’s smartphone operating system.

Their proposed framework also includes requirements that Google be required to disclose its consumer data and search information with other companies, including rivals located outside the U.S., for the next 10 years.

They told the court these steps could also stop Google from obtaining a monopoly in the AI space – acknowledging that technology is going to evolve, and therefore remedies must “include the ability to evolve alongside it as well.”

Google has proposed a much narrower remedies plan, including options for shorter contracts with browser companies, like Apple and Mozilla; new contracts with Android, and other important steps they said would make the landscape more competitive.

Google officials argue DOJ’s proposal goes “miles beyond” the relief that was ordered by Judge Amit Mehta in August, and warned that the government’s proposed framework would stifle competition, fail to regulate anticompetitive conduct, and hobble Google’s ability to attract new investments or innovate in key areas like AI and quantum computing.

JUDGES V TRUMP: HERE ARE THE KEY COURT BATTLES HALTING THE WHITE HOUSE AGENDA

Google CEO Sundar Pichai testified in court Wednesday that DOJ’s proposal, if adopted, would result in a “de facto divestiture” of Google’s search engine that would allow companies to reverse-engineer “any part” of its tech stack, which he noted is the result of decades of investment and innovation.

If that happened, he said, it could all but kill the nearly $2 trillion company by giving its IP away to its competitors.

“It’s not clear to me how to fund all the innovation we do,” he said, “if we were to give all of it away at marginal cost.”

O’Brien serves as the co-founder and partner emeritus of Larson LLP, a firm that has represented Google as special outside counsel in unrelated matters, though O’Brien himself has not been involved in any of those cases.

The Justice Department did not respond to Fox News Digital’s request for comment on the letter from O’Brien, or whether the Trump-led DOJ had plans to amend its proposed framework in the Google remedies case.